On the secret revolution of later life: when women step outside the gendered hierarchy and into freedom

Today’s post is a longer read than usual - almost an essay - tracing a line from Simone de Beauvoir’s forgotten insights on menopause to the hidden revolution of later life. It’s part feminist theory, part lived story, and perhaps also something else: a reflection on what it means to step outside old scripts into a freedom that can feel, at times, almost spiritual. I’d love to hear your thoughts - whether it resonates with your own experience, sheds light on the lives of women you know, or whether you see it differently.

Beauvoir said that one becomes a woman; everyone remembers that. But she also showed how one can step outside the sex-gender hierarchy - through midlife, through loss, through age - and that has been forgotten. Here, I’m describing the passage from the hag (a patriarchal identity: older woman as stigmatised) to the Hag (a reclaimed badge of honour: assertive, self-possessed, free). It is silent, unseen, but revolutionary. This is Beauvoir’s most radical, neglected insight: liberation not through youth, beauty, or parity within the system, but by stepping out of the system itself. Others have missed it. Here, I’m naming it.

Looking back on the path that brought me to mid-life - from the shame of being seen to the shame of no longer being worth seeing - I realise how each situation has been a reckoning with disappearance. As a girl. As a woman. As a lover. The question we can look to Beauvoir to answer is: what happens after that? Is there a life beyond it? A freedom not grounded in youth or erotic appeal?

And indeed there is. What comes next is not disappearance, but what remains. First the ghost of the woman she was made into, then the emergence of the woman she was always meant to be.

In this transformation, menopause is a key crucible. The hot flashes, the night sweating, the palpitations: this is an existential state, like being ill, or falling in love. And so it is for me. A volcano erupting in my body, waves of lava cooling to the taste of ash in my mouth. It leaves no trace but the thin sheen of sweat on my skin. I am being turned inside out, fighting with monsters. NHS pages list symptoms clinically: hot flushes, anxiety, palpitations, UTIs. Elizabethan doctors captured more of its surreal nature: “croaking of Frogges, hissing of Snakes...”

My body is changing, I am changing in my emotions, desires, relationship with the world. I feel confident speaking out at meetings, focused on words not appearances. When I get up I no longer test myself for euphoria, depression, anxiety. Yet no one notices. The transformation is invisible in plain sight.

Beauvoir knew the stakes. In The Second Sex she offers a startling reversal of menopause: “She is no longer prey to powers that submerge her: she is consistent with herself.”

That a woman of 38, which is what she was when she wrote The Second Sex, could see so far ahead remains remarkable. If reproduction hijacks the younger woman’s body, then its cessation isn’t a tragedy. It’s a bloody good thing. Miraculous, even.

Of course, menopause brings its own “difficult crisis”: upheaval, difficult symptoms, as mine are. But unlike puberty, this one can usher in freedom - from the species imperative, and potentially from (patriarchal) femininity itself. As with every life stage, there are choices. She can cling to old values, grasp tighter to femininity. Or she can look reality in the face and choose differently, finding in these changes not reduction but a new autonomy. The so-called “third sex.”

Beauvoir doesn’t develop this idea in detail. She uses the term sparingly in The Second Sex, barely at all in The Coming of Age. But we can work with it. The third sex, in Beauvoirian terms, is what a woman might become once she has cast off the limitations of the second.

This is not a return to girlhood. Time has passed; embodied time changes everything - presence, position, grasp on things. But it does require unlearning. The body once cumbersome, at times fragile, hormonal, shifting - from breasts to gut to mood to energy - can now stabilise. What was cyclical can unfold. The body stops being foregrounded. Dispositions, shaped under the male gaze that split her in two, can be reworked.

This, I think, is what Beauvoir means when she writes that “woman frees herself from her chains in her autumn and winter years.” If adolescence turns the body into a screen separating her from the world, then menopause lifts the fog. She engages the world directly. She ceases to second-guess herself through the observer’s eyes. She becomes whole. “They finally begin to view the world through their own eyes.”

The mending of the split can also be seen through Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar’s concept of “angel” and “monster.” Both angel and monster are patriarchal projections women must kill to become themselves.

The angel is young: modest, graceful, pure, selfless - beautiful because she surrenders. The monster is her distorted shadow: assertive, wilful, powerful, invariably older. Think Snow White and the wicked Queen. She terrifies.

And so hag and young beauty remain mythically fused. To destroy both - the ideal and the grotesque - is to make room for a woman defined by herself. Not an angel. Not a monster. Not an Other. But someone new.

To enter the third sex is to kill both angel and monster. To destroy projections and reclaim the self beneath. Not by returning to a fantasy of the past, but by walking forward into a new form of womanhood. One that begins not in puberty, but in its undoing.

Stepping outside the romantic script

At a Faculty meeting this semester, I walk in and notice the Romantic Philosophy Professor, with his air of suffering and wavy hair falling over one melancholy eye. The last time I’d seen him was the previous winter, crossing the little square to the station in the windy chill. He carried a heavy bag of books, stopped to puff on a rollie, gazed off into the purple sky in his threadbare Oxfam coat. His image stayed with me, reminding me of poetic boys from student days, though he was in his forties.

Today, seated across the table from him, I am untouched. He makes an impassioned but irrelevant point; other women gaze wistfully. I want to laugh. I speak next and ignore everything he has said. Clearly, I am not the woman I was six months before.

To understand how women cross the threshold into the so-called third sex – as I now realise I have – we need to understand Beauvoir’s idea of doubled consciousness and how it traps us in femininity.

This kicks in at puberty, she says. The girl’s body becomes public property. As Beauvoir puts it: “Her body is escaping her…; it becomes foreign to her; and at the same moment, she is grasped by others as a thing.” She begins to internalise the gaze of the other, learning to see herself from the outside as well as the inside. She becomes both subject and object simultaneously.

The psychologist Mary Pipher calls this a collapse of authenticity. In Reviving Ophelia, she writes that girls become “female impersonators,” cramming their whole selves into cramped, performative spaces. Instead of asking Who am I? What do I want?, they start asking What must I do to please others?

Jennifer McWeeny shows how this gets baked in. It’s not just explicit choices, but ingrained dispositions shaped by a world we didn’t choose. From shrinking under the male gaze to swallowing the idea that menstruation is dirty, we absorb what she calls “anonymous social meanings… already inside us.” Freeing ourselves requires both small acts of defiance - saying no, refusing to hide - and larger commitments, like Beauvoir’s decision to become the Independent Woman.

Raymond Williams helps us see how these shifts develop as “structures of feeling”: moods that at first seem private, vague, hard to name, but which over time become legible, part of how we understand the world.

The trouble is: the structure of feeling associated with becoming a Hag is still subterranean. It hasn’t been named, let alone institutionalised. There is some awareness now that menopause isn’t just a biological event but a developmental transition. But mainstream culture still treats it as pathology - something to be fixed or feared. There is no celebratory status equivalent to the “silver fox,” no social role for the wise, powerful older woman.

When I dismissed Professor Romantic at that meeting, the younger women frowned at me with fear and incomprehension. It would have been hard to convey to them what life looked like now, from my perspective and not theirs. As with so much of women’s knowledge, each generation must distil it anew. This passage is still happening all around us - but it remains invisible.

And yet: in memoir, in fiction, in fragments of women’s lives, we begin to see it. The transformation Beauvoir calls a “moral drama” is often precipitated by rupture — divorce, illness, redundancy, children leaving home, as well as the bodily changes of menopause. Any one of these can push a woman toward the threshold.

And these moments often bring shame. But shame isn’t only annihilating. It can rupture the script. It can spark the undoing of norms.

Menopause as new perception

At my workplace’s Menopause Club, I chat to two women at my table. Whilst the room is dominated by women loudly describing husbands, families, and the terrible effects of menopause, the three of us share different stories. We are curious about menopause, shocked by how unknown it was before it entered our lives, and how it is reshaping us at work.

Giulia, a Professor of Physics my age with dewy skin and a golden chestnut bob, tells us she struggled to keep her lab running when symptoms first hit. Sleepless nights left her panicked about professionalism. She turned to HRT - a pill each night, gel rubbed on her skin twice daily. When I ask what effect it’s had, she looks down. “It has helped me concentrate and function, no doubt. But…” she winces, “it has made me… more emotional. Tearful. More feminine than I was before, even.” Embarrassed, she adds, “I think I should go back to the doctor and adjust the dose.”

Justine, an administrator five years older, perfectly groomed with short neat hair and large glasses, says it was difficult at first but then improved. She compares it to driving through the deep Mersey Tunnel and finally emerging into daylight. She has not taken hormones. “I am not the way I was before. No: I am better.”

Sociologist Abigail Brooks confirms this link between embracing and resisting change in the “third age” mentality among ageing women. She focused on aesthetic procedures rather than HRT, but the conclusions apply. After interviewing women in the US, she contrasts two groups. Some cling to anti-ageing techniques, others resist and embrace maturity. They emphasise character, and describe authenticity. The benefits are tangible: less anxiety about appearance; less energy wasted contorting to the male gaze; a reclaimed body no longer available for others’ pleasure but for their own; and the visible signs of time. Wrinkles, greying hair, loose skin become not just ageing but evidence of having lived.

What emerges here is a key theme: bodily change brings psychic change. Embodiment and consciousness are inseparable. And for some women, the shift begins with menopause.

For former Guardian columnist Suzanne Moore, menopause triggered a reckoning. “Are we only defined by motherhood and fuckability? No, of course not. We are more than that … But what is this more?” she asks.

At the Menopause Club, Justine, when pressed, found it hard to define this more. After she spoke of the Mersey tunnel crossing, another woman who had just joined our table asked: “How exactly are you better?”

In her mid-40s, Lindy was slim and athletic with a bouncy pony-tail and had recently started HRT. She was devastated, she told us, that it had happened to her.

For a while, Justine was silent. Then she gave up searching for the right words: “I don’t feel pushed and pulled about by hormones anymore; I don’t feel the need to conform to the expectations younger women face.” The young woman frowned. “How is your energy?” she pressed. “Lower than it was,” Justine admitted. “Yes. But I’m working four days now so it doesn’t matter.” She hesitated, then said, “But I really don’t care what anyone thinks. That’s the point.”

The conversation stalled, foundering on the rocks of what “more” might mean. The younger woman wasn’t persuaded. “But I don’t want to change!” she insisted, her pony-tail wobbling. “I like the way I am!”

Perhaps persuasion isn’t possible unless one glimpses it for oneself.

I felt how the questions shift but don’t disappear. They deepen. These are the same questions adolescent girls wrestle with; and as Mary Pipher reminds us, their mothers rarely have answers.

These are what Beauvoir called the “agonising dilemma” of femininity. Pipher suggests if women in midlife can finally face them without denial, they may recover what they lost at puberty: pre-adolescent authenticity.

Beauvoir notes this task is easier for those who “have not essentially staked everything on their femininity.” But even then, it isn’t easy. The danger of backsliding is real: the temptation to cling to the second sex, to the habits that once offered safety, is everywhere. What matters is not simply awareness of ageing or invisibility, but the shift in consciousness - the moment when the silky ties of femininity begin to loosen.

At this point, there’s a choice. Either she fragments further - splitting her “real” self from her ageing body in order to preserve a youthful fiction - or she embraces actual change. The one offers safety. The other, transformation.

We see this vividly in Alix Kates Shulman’s Drinking the Rain. She retreats to a seaside cottage in Maine, far from her old New York life. The house, once full of noisy family holidays, becomes a crucible of solitude. She divorces. She walks away from old interests. She changes how she eats, sleeps, lives.

She slows down. She stops performing. She listens to her body’s rhythm. She begins to live in time, not race through it. And in the process, she recovers something obscured: her own appetite, her own desire, her own bodiliness beyond the male gaze.

In this remaking of herself, Shulman echoes Beauvoir’s own retreat to Marseille: her decision to shape herself as an independent woman, alone. Solitude isn’t withdrawal here. It is staging ground for sovereignty.

This, then, is the beginning of becoming the third. It doesn’t arrive all at once. It isn’t neat. It often starts with the body - its awkward strangeness, its refusal to be predictable. But if a woman can stay with that strangeness, resist scripts that tell her to panic, fix, disappear - then something new becomes possible. Not just survival, but re-embodiment. Not just ageing, but agency. Not just less of what she was, but more of who she is becoming.

When nature no longer feels like the enemy

I read about Shulman’s Maine beach house wistfully. As Christmas came and went and I prepared for a gruelling semester, I wished I too could retreat, rebuild myself from the foundations, away from the endless tasks of teaching and research.

As it happens, I do go on retreat: not by choice but because Covid comes. In March 2020, we enter lockdowns lasting eighteen months. It turns out that, whilst still maintaining my job, I can give myself up to the changes happening within in a way impossible in normal life. Lockdown gives me a gift: like sheltering in a warm, dark cave, out of which I occasionally peer with Zoom before retreating again, unseen, able to look deeply within.

I spend much of this time thinking about why the body, which I had long considered an enemy to me as a woman, no longer seems so. More than symptoms, it feels like an invitation into another state of being. All I have to do is follow. In the past I did all I could to resist it, for example, refusing to follow it into motherhood. But now I would not consider HRT. These changes favour the free self long struggling with her patriarchally feminine sister within me. That self is about to win.

Yet Beauvoir reminds us that entry into the third sex is a crisis. It may bring freedom, transformation - but it is no guarantee. Becoming an older woman cannot be assumed to be positive. What she makes of this phase is up to her, with little help from the world around her. Society barely even sees her.

At the same time, the elemental force of menopause — night sweats, memory glitches, lost libido — can make some women, including feminists, look differently at biology. Hormones shaped us all along. Maybe that was the root of our oppression. And now, with oestrogen in retreat, maybe the oppression lifts. Maybe femininity was just hormones. Maybe nature has finally become our friend.

But this is fantasy. Women’s post-reproductive lifespan wasn’t selected for us. It was built around men’s longer fertility span, as they produce viable sperm into old age. Menopause is almost certainly a by-product, a side-effect of finite ovarian reserves. When it’s gone, it’s gone.

The truth is that menopause gives nothing by itself. Nature didn’t grant us a second life. What comes after is never automatic, never guaranteed. Freedom here is not a gift but a choice - fragile, hard-won, worth fighting for. Some women will be dragged back into care and obligation; others will find in this threshold the chance to begin again. What matters is not biology but becoming.

Beauvoir was right: woman is not a fixed reality but a movement, a surpassing, something more.

In these later years, she is not less than she was. She is something new.

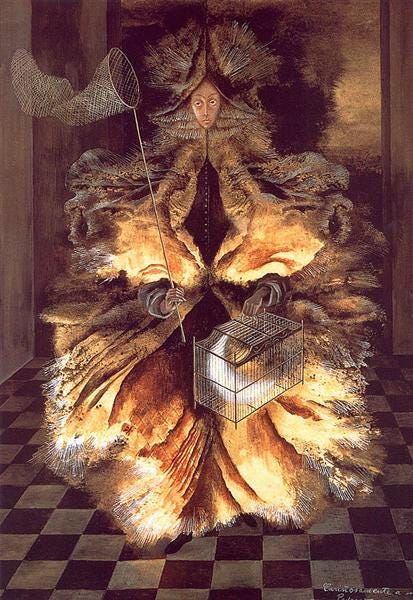

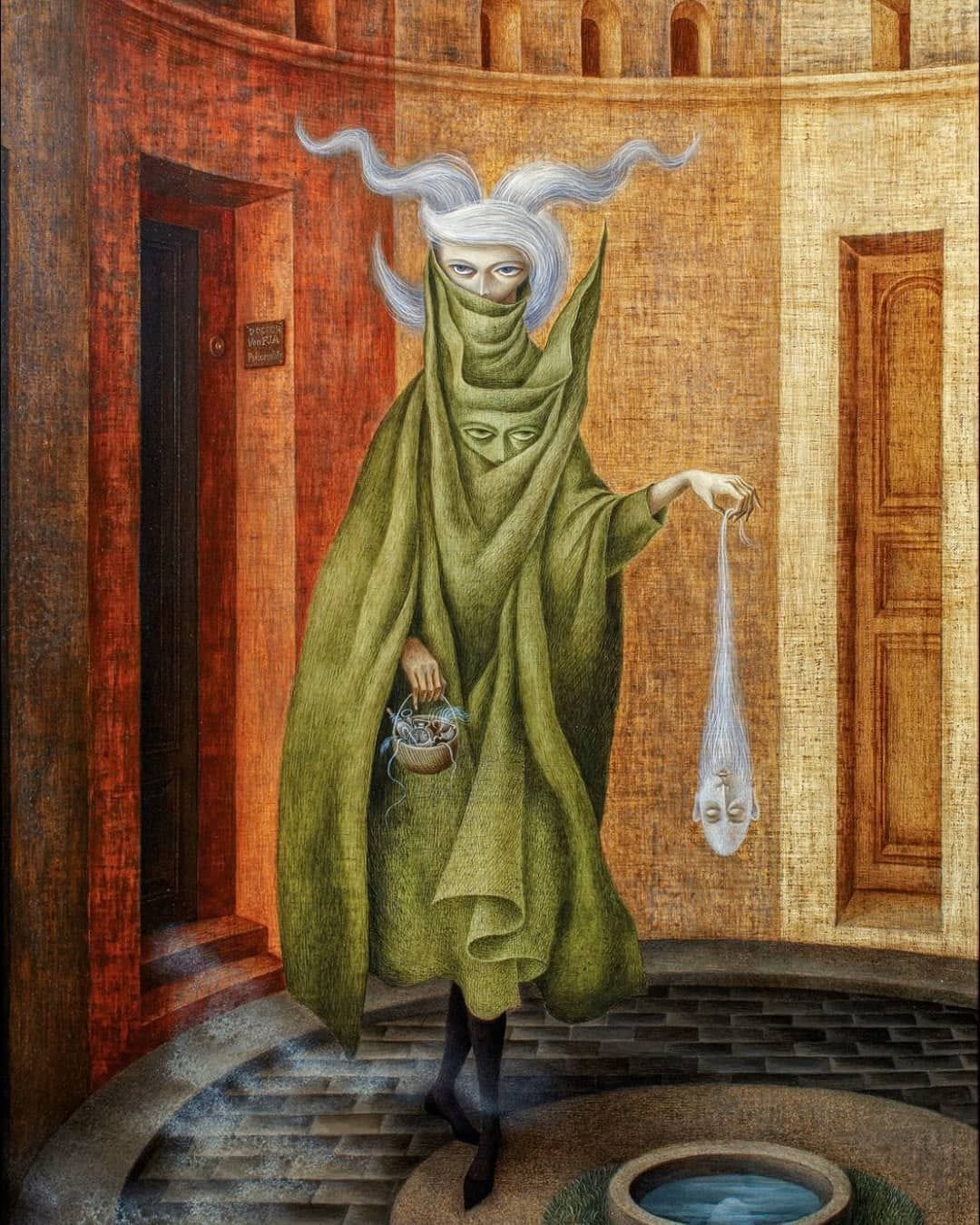

Images: Remedios Varo (1908–1963)

Everything here is free. If you’d like to support this work, the simplest way is to subscribe — and share with others who might be interested.

Remedios Varo! Great surrealist woman artist, almost forgotten.

A bit late to the party, but I was working all week and saving this to read on Friday night in place of my traditional (pre-menopausal) martini which I can no longer metabolize, dammit. Riveting as hoped, and I have so many agreements but also some dissonance. So many thoughts, but as someone who now lives close to the land, children and animals I feel I must point out that women live long lives because our *wisdom* is crucial to our tribe's survival. It is not easy to learn to grow, harvest and put up food or tend a thriving flock/herd or raise healthy children. Old women were prized for their knowledge and skills until about 5 seconds ago in human history. Even now in my rural New England town people remember the elder women's quilting skills and their jam recipes. The idea that we're useless after menopause is a distinctly urban phenomenon. I often think that the cat lady stereotype has truth to it because older women are meant to tend animals. It's what old women and children have always done since goats were domesticated by humans 10,000 years ago. We aren't meant to be sexy forever, which means invisibility in modern culture, but that doesn't preclude usefulness, happiness and deep satisfaction with life. Children and animals don't care what you look like. Getting closer to infirmity and death is invariably a downer for the sentient beings we are, of course. "Thou are blessed compared with me, the present only toucheth thee," as Robert Burns famously said to a mouse. We're cursed with knowing what's to come, but damned if we don't enjoy each season of life for the pleasures it brings.